Non-Aligned Movement

|

Non-Aligned Movement

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Coordinating Bureau | New York City, United States | |||

| Membership | 118 members 18 observer countries |

|||

| Leaders | ||||

| - | Secretary-General | Hosni Mubarak | ||

| Establishment | 1961 in Belgrade. Serbia | |||

| Website www.namegypt.org |

||||

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is an intergovernmental organization of states considering themselves not aligned formally with or against any major power bloc. As of 2010, the organization has 118 members and 18 observer countries.[1] Generally speaking (as of 2010), the Non-Aligned Movement members can be described as all of those countries which belong to the Group of 77 (along with Belarus and Uzbekistan), but which are not observers in Non-Aligned Movement and are not oceanian (with the exception of Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu).

The organization was founded in Belgrade in 1961, and was largely the brainchild of Indonesia's first President, Soekarno, India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, Egypt's second President, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Yugoslavia's first President, Josip Broz Tito. All four leaders were prominent advocates of a middle course for states in the Developing World between the Western and Eastern blocs in the Cold War.

The purpose of the organisation as stated in the Havana Declaration of 1979 is to ensure "the national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of non-aligned countries" in their "struggle against imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, racism, and all forms of foreign aggression, occupation, domination, interference or hegemony as well as against great power and bloc politics."[2] They represent nearly two-thirds of the United Nations's members and 55% of the world population, particularly countries considered to be developing or part of the third world.[3]

Members have, at various times, included: Yugoslavia, Argentina, SWAPO, Cyprus, and Malta. Brazil has never been a formal member of the movement, but shares many of the aims of Non-Aligned Movement and frequently sends observers to the Non-Aligned Movement's summits. While the organization was intended to be as close an alliance as NATO (1949) or the Warsaw Pact (1955), it has little cohesion and many of its members were actually quite closely aligned with one or another of the great powers. Additionally, some members were involved in serious conflicts with other members (e.g. India and Pakistan, Iran and Iraq). The movement fractured from its own internal contradictions when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. While the Soviet allies supported the invasion, other members of the movement (particularly predominantly Muslim states) condemned it.

Because the Non-Aligned Movement was formed as an attempt to thwart the Cold War,[4] it has struggled to find relevance since the Cold War ended. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, a founding member, its membership was suspended[5] in 1992 at the regular Ministerial Meeting of the Movement, held in New York during the regular yearly session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. At the Summit of the Movement in Jakarta, Indonesia (September 1, 1992 – September 6, 1992) Yugoslavia was suspended or expelled from the Movement.[6] The successor states of the SFR Yugoslavia have expressed little interest in membership, though some have observer status. In 2004, Malta and Cyprus ceased to be members and joined the European Union. Belarus remains the sole member of the Movement in Europe. Turkmenistan, Belarus and Dominican Republic are the most recent entrants. The application of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Costa Rica were rejected in 1995 and 1998. Serbia has been suspended since 1992 due to the Serbian Government's involvement in the Bosnian War (officially as the Government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia at the time).[7]

Contents |

Origins

Independent countries, who chose not to join any of the Cold War blocs, were also known as non aligned nations.

The term "non-alignment" itself was coined by Indian Prime Minister Nehru during his speech in 1954 in Colombo, Sri Lanka. In this speech, Nehru described the five pillars to be used as a guide for Sino-Indian relations, which were first put forth by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. Called Panchsheel (five restraints), these principles would later serve as the basis of the Non-Aligned Movement. The five principles were:

- Mutual respect for each other's territorial integrity and sovereignty

- Mutual non-aggression

- Mutual non-interference in domestic affairs

- Equality and mutual benefit

- Peaceful co-existence

A significant milestone in the development of the Non-aligned movement was the 1955 Bandung Conference, a conference of Asian and African states hosted by Indonesian president Sukarno. Sukarno has given a significant contribution to promote this movement. The attending nations declared their desire not to become involved in the Cold War and adopted a "declaration on promotion of world peace and cooperation", which included Nehru's five principles. Six years after Bandung, an initiative of Yugoslav president Tito led to the first official Non-Aligned Movement Summit, which was held in September 1961 in Belgrade.

At the Lusaka Conference in September 1970, the member nations added as aims of the movement the peaceful resolution of disputes and the abstention from the big power military alliances and pacts. Another added aim was opposition to stationing of military bases in foreign countries.[4]

The founding fathers of the Non-aligned movement were: Sukarno of Indonesia, Nehru of India, and Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. Their actions were known as 'The Initiative of Five'.

Organizational structure and membership

The organizational structure and membership are complementary aspects of the group.[8]

Requirements of the Non-Aligned Movement with the key beliefs of the United Nations. The latest requirements are now that the candidate country has displayed practices in accordance with:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations, large and small.

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

- Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country.

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

- Promotion of mutual interests and co-operation.

- Respect for justice and international obligations.

Policies and ideology

Secretaries General of the NAM had included such diversified figures as Suharto, an authoritarian anti-communist, and Nelson Mandela, a democratic socialist and famous anti-apartheid activist. Consisting of many governments with vastly different ideologies, the Non-Aligned Movement is unified by its commitment in world peace and security. At the seventh summit held in New Delhi in March 1983, the movement described itself as the "history's biggest peace movement".[9] The movement places equal emphasis on disarmament. NAM's commitment to peace pre-dates its formal institutionalisation in 1961. The Brioni meeting between heads of governments of India, Egypt and Yugoslavia in 1956 recognized that there exists a vital link between struggle for peace and endeavours for disarmament.[9]

The Non-aligned movement believes in policies and practices of cooperation, especially those that are multilateral and provide mutual benefit to all those involved. Many of the members of the Non-Aligned Movement are also members of the United Nations and both organisations have a stated policy of peaceful cooperation, yet successes that the NAM has had in multilateral agreements tends to be ignored by the larger, western and developed nation dominated UN[10]. African concerns about apartheid were linked with Arab-Asian concerns about Palestine[10] and success of multilateral cooperation in these areas has been a stamp of moderate success. The Non-Aligned Movement has played a major role in various ideological conflicts throughout its existence, including extreme opposition to apartheid regimes and support of liberation movements in various locations including Zimbabwe and South Africa. The support of these sorts of movements stems from a belief that every state has the right to base policies and practices with national interests in mind and not as a result of relations to a particular power bloc[3]. The Non-aligned movement has become a voice of support for issues facing developing nations and is still contains ideals that are legitimate within this context.

Contemporary relevance

Since the end of the Cold War and the formal end of colonialism, the Non-aligned movement has been forced to redefine itself and reinvent its purpose in the current world system. A major question has been whether many of its foundational ideologies, principally national independence, territorial integrity, and the struggle against colonialism and imperialism, can be applied to contemporary issues. The movement has emphasised its principles of multilateralism, equality, and mutual non-aggression in attempting to become a stronger voice for the global South, and an instrument that can be utilised to promote the needs of member nations at the international level and strengthen their political leverage when negotiating with developed nations. In its efforts to advance Southern interests, the movement has stressed the importance of cooperation and unity amongst member states,[11] but as in the past, cohesion remains a problem since the size of the organisation and the divergence of agendas and allegiances present the ongoing potential for fragmentation. While agreement on basic principles has been smooth, taking definitive action vis-à-vis particular international issues has been rare, with the movement preferring to assert its criticism or support rather than pass hard-line resolutions.[12] The movement continues to see a role for itself, as in its view, the world’s poorest nations remain exploited and marginalised, no longer by opposing superpowers, but rather in a uni-polar world,[13] and it is Western hegemony and neo-colonialism that that the movement has really re-aligned itself against. It opposes foreign occupation, interference in internal affairs, and aggressive unilateral measures, but it has also shifted to focus on the socio-economic challenges facing member states, especially the inequalities manifested by globalisation and the implications of neo-liberal policies. The non-aligned movement has identified economic underdevelopment, poverty, and social injustices as growing threats to peace and security.[14]

Current activities and positions

- Criticism of US policy

In recent years the US has become a target of the organisation. The US invasion of Iraq and the War on Terrorism, its attempts to stifle Iran and North Korea's nuclear plans, and its other actions have been denounced as human rights violations and attempts to run roughshod over the sovereignty of smaller nations.[15] The movement’s leaders have also criticised the American control over the United Nations and other international structures. While the organisation has rejected terrorism, it condemns the association of terrorism with a particular religion, nationality, or ethnicity, and recognises the rights of those struggling against colonialism and foreign occupation.[11]

- Self-determination of Puerto Rico

Since 1961, the group have supported the discussion of the case of Puerto Rico's self-determination before the United Nations. A resolution on the matter will be proposed on the XV Summit by the Hostosian National Independence Movement.[16]

- Anti-Zionism

The Non-Aligned Movement's Havana Declaration of 1979 adopted anti-Zionism as part of the movement's agenda. The movement has denounced Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[17] It has called upon Israel to halt its settlement activities, open up border crossings, and cease the use of force and violence against civilians. The UN has also been asked to pressure Israel and to do more to prevent human rights abuses.

- Sustainable development

The movement is publicly committed to the tenets of sustainable development and the attainment of the Millennium Development Goals, but it believes that the international community has not created conditions conducive to development and has infringed upon the right to sovereign development by each member state. Issues such as globalisation, the debt burden, unfair trade practices, the decline in foreign aid, donor conditionalities, and the lack of democracy in international financial decision-making are cited as factors inhibiting development.[18]

- Reforms of the UN

The Non-Aligned Movement has been quite outspoken in its criticism of current UN structures and power dynamics, mostly in how the organisation has been utilised by powerful states in ways that violate the movement’s principles. It has made a number of recommendations that would strengthen the representation and power of ‘non-aligned’ states. The proposed reforms are also aimed at improving the transparency and democracy of UN decision-making. The UN Security Council is the element considered the most distorted, undemocratic, and in need of reshaping.[19]

- South-south cooperation

Lately the Non-Aligned Movement has collaborated with other organisations of the developing world, primarily the Group of 77, forming a number of joint committees and releasing statements and document representing the shared interests of both groups. This dialogue and cooperation can be taken as an effort to increase the global awareness about the organisation and bolster its political clout.

- Cultural diversity and human rights

The movement accepts the universality of human rights and social justice, but fiercely resists cultural homogenisation. In line with its views on sovereignty, the organisation appeals for the protection of cultural diversity, and the tolerance of the religious, socio-cultural, and historical particularities that define human rights in a specific region.[20]

- Working groups, task forces, committees[21]

- High-Level Working Group for the Restructuring of the United Nations

- Working Group on Human Rights

- Working Group on Peace-Keeping Operations

- Working Group on Disarmament

- Committee on Palestine

- Task Force on Somalia

- Non-Aligned Security Caucus

- Standing Ministerial Committee for Economic Cooperation

- Joint Coordinating Committee (chaired by Chairman of G-77 and Chairman of NAM)

Summits

Belgrade, September 1-6, 1961

Belgrade, September 1-6, 1961 Cairo, October 5-10, 1964

Cairo, October 5-10, 1964 Lusaka, September 8-10, 1970

Lusaka, September 8-10, 1970 Algiers, September 5-9, 1973

Algiers, September 5-9, 1973 Colombo, August 16-19, 1976

Colombo, August 16-19, 1976 Havana, September 3-9, 1979

Havana, September 3-9, 1979 New Delhi (originally planned for Baghdad), March 7-12, 1983

New Delhi (originally planned for Baghdad), March 7-12, 1983 Harare, September 1-6, 1986

Harare, September 1-6, 1986 Belgrade, September 4-7, 1989

Belgrade, September 4-7, 1989 Jakarta, September 1-6, 1992

Jakarta, September 1-6, 1992 Cartagena de Indias, October 18-20, 1995

Cartagena de Indias, October 18-20, 1995 Durban, September 2-3, 1998

Durban, September 2-3, 1998 Kuala Lumpur, February 20-25, 2003

Kuala Lumpur, February 20-25, 2003 Havana, September 15-16, 2006

Havana, September 15-16, 2006 Sharm El Sheikh, July 11-16, 2009

Sharm El Sheikh, July 11-16, 2009 Kish Island, 2012

Kish Island, 2012

Secretaries-General

Between summits, the Non-Aligned Movement is run by the secretary-general elected at last summit meeting. As a considerable part of the movement's work is undertaken at the United Nations in New York, the chair country's ambassador to the UN is expected to devote time and effort to matters concerning the Non-Aligned Movement. A Co-ordinating Bureau, also based at the UN, is the main instrument for directing the work of the movement's task forces, committees and working groups.

| Secretaries-General of the Non-Aligned Movement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Country | Party | From | To |

| Josip Broz Tito | League of Communists of Yugoslavia | 1961 | 1964 | |

| Gamal Abdel Nasser | Arab Socialist Union | 1964 | 1970 | |

| Kenneth Kaunda | United National Independence Party | 1970 | 1973 | |

| Houari Boumédienne | Revolutionary Council | 1973 | 1976 | |

| William Gopallawa | Independent | 1976 | 1978 | |

| Junius Richard Jayawardene | United National Party | 1978 | 1979 | |

| Fidel Castro | Communist Party of Cuba | 1979 | 1983 | |

| N. Sanjiva Reddy | Janata Party | 1983 | ||

| Zail Singh | Congress Party | 1983 | 1986 | |

| Robert Mugabe | ZANU-PF | 1986 | 1989 | |

| Janez Drnovšek | Independent | 1989 | 1990 | |

| Borisav Jović | Socialist Party of Serbia | 1990 | 1991 | |

| Stjepan (Stipe) Mesić | Croatian Democratic Union | 1991 | ||

| Branko Kostić | Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro | 1991 | 1992 | |

| Dobrica Ćosić | Socialist Party of Serbia | 1992 | ||

| Suharto | Golkar | 1992 | 1995 | |

| Ernesto Samper Pizano | Colombian Liberal Party | 1995 | 1998 | |

| Andrés Pastrana Arango | Colombian Conservative Party | 1998 | ||

| Nelson Mandela | African National Congress | 1998 | 1999 | |

| Thabo Mbeki | African National Congress | 1999 | 2003 | |

| Mahathir bin Mohammad | United Malays National Organisation | 2003 | ||

| Abdullah Ahmad Badawi | United Malays National Organisation | 2003 | 2006 | |

| Fidel Castro[22] | Communist Party of Cuba | 2006 | 2008 | |

| Raúl Castro | Communist Party of Cuba | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Hosni Mubarak | National Democratic Party | 14 July 2009 | present | |

Members

Afghanistan

Afghanistan Algeria

Algeria Angola

Angola Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Bahamas

Bahamas Bahrain

Bahrain Bangladesh

Bangladesh Barbados

Barbados Belarus

Belarus Belize

Belize Benin

Benin Bhutan

Bhutan Bolivia

Bolivia Botswana

Botswana Burma (Myanmar)

Burma (Myanmar) Brunei

Brunei Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Burundi

Burundi Cambodia

Cambodia Cameroon

Cameroon Cape Verde

Cape Verde Central African Republic

Central African Republic Chad

Chad Chile

Chile Colombia

Colombia Comoros

Comoros Congo

Congo Côte d'Ivoire

Côte d'Ivoire Cuba

Cuba Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo Djibouti

Djibouti Dominica

Dominica Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Ecuador

Ecuador Egypt

Egypt Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea Eritrea

Eritrea Ethiopia

Ethiopia Gabon

Gabon Gambia

Gambia Ghana

Ghana Grenada

Grenada Guatemala

Guatemala Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Guyana

Guyana Haiti

Haiti Honduras

Honduras India

India Indonesia

Indonesia Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Jamaica

Jamaica Jordan

Jordan Kenya

Kenya Kuwait

Kuwait Laos

Laos Lebanon

Lebanon Lesotho

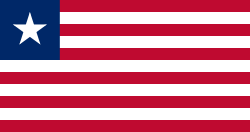

Lesotho Liberia

Liberia Libya

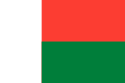

Libya Madagascar

Madagascar Malawi

Malawi Malaysia

Malaysia Maldives

Maldives Mali

Mali Mauritania

Mauritania Mauritius

Mauritius Mongolia

Mongolia Morocco

Morocco Mozambique

Mozambique Namibia

Namibia Nepal

Nepal Nicaragua

Nicaragua Niger

Niger Nigeria

Nigeria North Korea

North Korea Oman

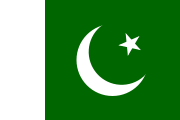

Oman Pakistan

Pakistan Palestine

Palestine Panama

Panama Papua New Guinea

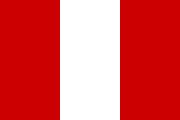

Papua New Guinea Peru

Peru Philippines

Philippines Qatar

Qatar Rwanda

Rwanda Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Senegal

Senegal Seychelles

Seychelles Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Singapore

Singapore Somalia

Somalia South Africa

South Africa Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Sudan

Sudan Suriname

Suriname Swaziland

Swaziland Syria

Syria Tanzania

Tanzania Thailand

Thailand Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Togo

Togo Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia

Tunisia Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Uganda

Uganda United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Vanuatu

Vanuatu Venezuela

Venezuela Vietnam

Vietnam Yemen

Yemen Zambia

Zambia Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Former members

Argentina

Argentina North Yemen

North Yemen South Yemen

South Yemen Cyprus

Cyprus Malta

Malta Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Observers

The following countries and organizations have observer status:[23]

Countries

Organizations

- African Union

- Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization

- Common- Wealth Secretariat

- Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front

- League of Arab States

- Hostosian National Independence Movement

- Organization of the Islamic Conference

- South Center

- United Nations

- World Peace Council

Guests

There is no permanent guest status,[24] but often several non-member countries are represented as guests at conferences. In addition, a large number of organisations, both from within the UN system and from outside, are always invited as guests.

See also

- G-77

- Role of India in Non-aligned movement

- South-South Cooperation

- Third World

- New World Information and Communication Order

Further reading

- Hans Köchler (ed.), The Principles of Non-Alignment. The Non-aligned Countries in the Eighties—Results and Perspectives. London: Third World Centre, 1982. ISBN 0-86199-015-3 (Google Print)

References

- ↑ http://www.namegypt.org/en/AboutName/MembersObserversAndGuests/Pages/default.aspx

- ↑ Fidel Castro speech to the UN in his position as chairman of the non-aligned countries movement 12 October 1979; Pakistan & Non-Aligned Movement, Board of Investment - Government of Pakistan, 2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Grant, Cedric. "Equity in Third World Relations: a third world perspective." International Affairs 71, 3 (1995), 567-587.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Suvedi, Suryaprasada (1996). Land and Maritime Zones of Peace in International Law. Oxford University Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 0198260962.

- ↑ http://www.nam.gov.za/background/members.htm

- ↑ Lai Kwon Kin (September 2, 1992). "Yugoslavia casts shadow over non-aligned summit". The Independent @ Independent.co.uk. Independent News and Media Limited. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/yugoslavia-casts-shadow-over-nonaligned-summit-1548802.html. Retrieved 2009-09-26. "Iran and several other Muslim nations want the rump state of Yugoslavia kicked out, saying it no longer represents the country which helped to found the movement."

- ↑ Najam, Adil (2003). "Chapter 9: The Collective South in Multinational Environmental Politics". In Nagel, Stuard. Policymaking and prosperity : a multinational anthology. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. p. 233. ISBN 0-7391-0460-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=eCVZ5Vir2e0C&pg=PA233&f=false#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2009-11-10. "Turkmenistan, Belarus and Dominican Republic are the most recent entrants. The application of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Costa Rica were rejected in 1995 and 1998. Yugoslavia has been suspended since 1992."

- ↑ NAM Background Information

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ohlson, Thomas; Stockholm (1988). Arms Transfer Limitations and Third World Security. Oxford University Press. pp. 198. ISBN 0198291248.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Morphet, Sally. “Multilateralism and the Non-Aligned Movement: What Is the Global South Doing and Where Is It Going?” Global Governance 10 (2004), 517–537

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 http://www.ipsterraviva.net/TV/Noal/en/default.asp. See "Putting Differences Aside," Daria Acosta, September 18, 2006.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/2798187.stm#facts. BBC Profile, BBC News, January 30, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.nam.gov.za/xiisummit/chap1.htm. See no.10-11 in Durban Summit 'Final Document.'

- ↑ http://www.nam.gov.za/xiisummit/chap1.htm. See no.16-22 in Durban Summit 'Final Document.'

- ↑ http://www.cbc.ca/world/story/2006/09/16/nonalign.html. "Non-aligned nations slam U.S.," CBC News, September 16, 2006.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ http://espana.cubanoal.cu/ingles/index.html. See "Statement on the situation in the occupied Palestinian territory.

- ↑ http://espana.cubanoal.cu/ingles/index.html. See "Statement on the implementation of the Right to Development," January 7, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.nam.gov.za/xiisummit/chap1.htm. See no.55 in Durban Summit 'Final Document.'

- ↑ http://espana.cubanoal.cu/ingles/index.html. See "Declaration on the occasion of celebrating Human Rights Day."

- ↑ http://www.nam.gov.za/background/background.htm#2.4. NAM background information.

- ↑ Fidel Castro, having recently undergone gastric surgery, was unable to attend the conference and was represented by his younger brother, Cuba's acting president Raúl Castro. See "Castro elected President of Non-Aligned Movement Nations", People's Daily, 16-09-2006.

- ↑ Member and Observer Countries, Non-Aligned Movement

- ↑ NAM Background Information

External links

- Official Site: 14th Summit — Fourteenth Non Aligned Movement Summit, (Havana, September 11-16, 2006) (Spanish)

- Non-Aligned Movement — Resource site

- International Institute for Non-Aligned Studies — Think Tank for Non-Aligned Movement

- Statement of UN Secretary General to NAM, September 28, 2007.

- Meeting of NAM at the 58 General Assembly of UN, November 26, 2003.

- The Cold War International History Project's Document Collection on the NAM

|

||||||||||||||||||||